Pintar paisajes

Often nature itself gets in the way.

Often nature itself gets in the way.

https://instagram.com/p/1zwUqvMliL/

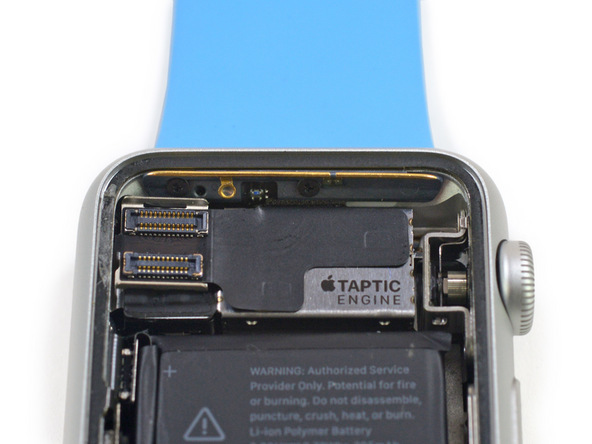

Los de iFixit se sacrifican para que nosotros no tengamos que desmontarlo en casa:

Time flies: it’s been eight months since Apple announced its (digital) crowning achievement, the Apple Watch. Join us as we make time stand still by tearing down the Apple Watch—and see what makes it tick.

“The Ghosts of Pretty Cello Girls”

To say that Lena Griffin plays the cello on “The Ghosts of Pretty Cello Girls” is to only tell half the track’s story. This is because half the track isn’t cello.

Radioactive Ming vases echo our toxic dependency on electronics – we make money not art

Last year, the Unknown Fields Division, a nomadic design studio that explores peripheral landscapes, industrial ecologies and precarious wilderness, travelled to Asia to follow the path of the symbol of globalization: the massive container ship. The group came back with amazing stories, images, videos and with a set of radioactive Ming vases made from the toxic waste of our electronic gadgets.

Each object is made from the amount of toxic waste created in the production of three items of technology – a smartphone, a featherweight laptop and the cell of a smart car battery. Besides, the vases are sized in relation to the amount of waste created in the production of each item.

Rare Earthenware – Full Film from Toby Smith on Vimeo.

Lo que más me ha gustado deHow Not to Write About Smartphones and Spain · Global Voices no es lo que dice del uso de los teléfonos en España (que puede ser más o menos interesante) sino más bien el poner en evidencia nuestra tendencia a tratar los lugares relativamente lejanos como a) totalmente uniformes y b) como extraños en sí mismo.

Es una tendencia habitual de la ciencia ficción, donde viajar a un planeta lejano es como ir a un lugar con climatología y ecología simple, donde todo es de una única forma concreta. No hay más que pensar en Star Wars, en la que un número limitado de personajes y escenarios ocupa toda una galaxia, y donde los planetas vienen marcados por: hielo, desierto, agua…

En la ficción puede considerase excusable, pero más grave es cuando lo hacemos con otros países y regiones, cuando recurrimos a una especie de esencialismo primitivo, considerando que sólo ciertas facetas del lugar son representativas y excluimos lo que no nos encaja. Lo hacemos mucho con China y Japón, que no sólo tendemos a considerar culturas monolíticas, sino que además tratamos como territorios lejanos donde suceden cosas extrañas que no podemos entender (y por tanto, cualquier noticia “rara” situada en uno de esos países nos resulta automáticamente creíble sea verdad o no). Otro ejemplo es nuestra tendencia a considerar que lo que pasa en España no pasa en otros países de nuestro entorno, como si el resto de Europa viviese en la utopía.

Básicamente, nos aprovechamos de los lugares lo suficientemente remotos para situar allí el paraíso o el infierno.

Como decía, lo gracioso de este artículo es que trata, y desmonta, una de esas situaciones, pero en la que nosotros somos los protagonistas, donde nosotros somos el objeto de alteridad fantástica y monolítica. Es una buena oportunidad para ver el mecanismo funcionando en sentido contrario:

It’s not often that I speak in Internet, but an incredulous O RLY? escaped my lips. The tweet linked to a column in Pacific Standard magazine, which covers social, economic and political issues in the United States, that asserts “the biggest difference” between how Americans and Spaniards use technology is “that no one seems to be on their phones” in Spain. “What locals were doing instead was talking to each other, loudly and heatedly, continuously,” the Brooklyn-based author writes, his observations based on a trip through Spain and Portugal. “It struck me as the kind of socializing we desire when we bemoan our smartphone ‘addictions.’”

The piece almost reads like a satire of a Western correspondent parachuting into an “exotic” locale and reporting back sweeping generalizations about the place. It portrays Spain—still known to many as the land of the midday siesta, even though only about 16% of the population still take a nap every day—and greater Europe as some sort of 21st-century noble savage, in tune with the natural art of conversation and uncorrupted by the same technology that is turning Americans into bleary-eyed zombies.

But when it comes to technology and smartphone addiction, that’s not the case. “Nobody over there seems to be talking about addiction to technology,” you say? Sure, if you don’t pay any attention to Spanish media and haven’t spent more than a holiday’s worth of time with Spaniards, you could say that. A quick Google search returns more than a few mainstream discussions of the issue (in Spanish, of course).

Una vez hice un vídeo sobre Lanzarote, mi tierra, donde mostraba algunas cosas que hay en Lanzarote (un tigre blanco, por ejemplo) pero que no se corresponden con la imagen de Lanzarote. Sin embargo, son elementos presentes y que además llevan allí mucho tiempo. Recibí algún comentario al respecto, más que nada porque nos cuesta aceptar que los lugares reales rara vez se ajustan a la imagen que tenemos de ellos. Pero es un hecho que la isla ha cambiado mucho desde que yo era niño.

2014 – NERDGIRLS – herstory of electronic music

The “NERDGIRLS Mash by poemproducer AGF 8 March 2014 – for equality, diversity and world peace” includes about 50 artists spanning about 50 years of outstanding, smart, fun, female and pioneering electronic music and is dedicated to my daughter.

Puedes encontrar la lista completa de artistas incluidas. Una hora y algo de música muy entretenida e interesante.

NERDGIRLS Mash by poemproducer AGF 8 March 2014 – for equality, diversity and world peace by Poemproducer Aka Agf on Mixcloud

(vía Nedgirls – herstory of electronic music by Antye Greie-Ripatti | ./mediateletipos))))

Dark Jovian de Amon Tobin.

I made these tracks a year or two ago after binge-watching space exploration films. People have, from time to time, described things I’ve done as “scores for imaginary movies,” which has always irritated me, but on this occasion it’s sort of true.

Even so, what I was really trying to do was to interpret a sense of scale, like moving towards impossibly giant objects until they occupy your whole field of vision, planets turning, or even how it can feel just looking up at night.

Visto en Goldsmith-Ligeti EDM.

2 Simple Rules That Great Readers Live By (But Never Tell)

Son dos reglas sencillas. Pero voy a empezar por la segunda: saber dejar de leer. En serio, si un libro no te gusta es legítimo dejar de leerlo. Lo puedes regalar, abandonar en el banco de un parque o incluso tirarlo a la basura (si el libro es muy malo, lo lógico es tirarlo. ¿Le regalarías a un amigo fruta podrida? ¿Verdad que no? Pues igual). No es obligatorio terminar los libros, por poco que quede para acabar. Un libro tiene que ganarse el tiempo que le dedicas.

Como se decide en qué momento dejar de leer ya es cuestión personal. En mi caso, paro en cuanto sospecho que aquello no lleva a ningún sitio. Como si quedan 10 páginas para acabar…:

The old rule ‘100 pages minus your age’, is a good one here. Life is too short to be stuck in books that aren’t going anywhere, that aren’t adding value to your mind. When you’re young, you have more time, obviously, and you also know less what you need and like. But the costs of dilettantism rise with age.

As you get older, you’ll become a more critical reader–not accepting things just because other people say it is good, or more importantly, not agreeing with an author just because they’ve been published. Authors owe a duty to their reader to marshall their arguments properly, to deliver the goods. If they fail to do this–move on. There are plenty of other writers (historians, thinkers, philosophers, entertainers, leaders, poets, storytellers) willing to step up and take their place.

La primera regla es comprar los libros a medida que te interesan. Así ya están en casa y los puedes leer cuando te entren las ganas. La lógica es que en casa están mejor que en la librería.

Sin embargo, eso cuesta dinero, aunque normalmente los lectores no suelen tener problema para gastar en libros. Pero yo la considero una regla más débil precisamente por la razón que la segunda es cada vez más fuerte: la edad. Con los años vas aprendiendo que tampoco hace falta leerlo todo, que ese esfuerzo tampoco lleva a ningún lado. Es más, que un libro te interese en la librería no significa que vaya interesarte días o semanas después, cuando te pongas a leerlo. Que si los libros se pueden dejar de leer, también se pueden dejar de comprar.

Aunque, confieso que yo tengo grandes problemas para no comprar libros.