La muerte de Sócrates

Cuando leí por primera vez la Apología de Sócrates, lo que se me vino a la cabeza es que de haber estado yo en ese tribunal, también le habría condenado a muerte, aunque sólo fuese para que se callase de una vez. Lo segundo que pensé es que estaba leyendo el relato de un suicidio cuidadosamente planeado. Sócrates odiaba de tal forma a sus conciudadanos y a la ciudad que tanto decía respetar que se hizo matar para dejarles mal. No le bastaba con el odio, debía disfrutar del placer de convertirlos en inferiores. De esa forma, en cuanto una posibilidad de salir de esa situación levantaba la cabeza, Sócrates no dudaba en estrangularla y luego patearla hasta matarla. En cierto forma, hay que admirar una iniquidad de semejante calibre.

Cuando leí por primera vez la Apología de Sócrates, lo que se me vino a la cabeza es que de haber estado yo en ese tribunal, también le habría condenado a muerte, aunque sólo fuese para que se callase de una vez. Lo segundo que pensé es que estaba leyendo el relato de un suicidio cuidadosamente planeado. Sócrates odiaba de tal forma a sus conciudadanos y a la ciudad que tanto decía respetar que se hizo matar para dejarles mal. No le bastaba con el odio, debía disfrutar del placer de convertirlos en inferiores. De esa forma, en cuanto una posibilidad de salir de esa situación levantaba la cabeza, Sócrates no dudaba en estrangularla y luego patearla hasta matarla. En cierto forma, hay que admirar una iniquidad de semejante calibre.

Y por otra parte, ¿por qué no concederle lo que pide?

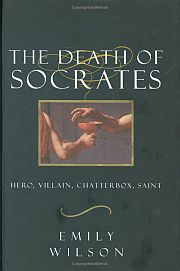

Pero bueno, yo realmente venía a hablar de otro libro. Me lo acabo de encontrar en 3quarksdaily (bitácora que te interesa si todavía respiras) y se llama The Death of Socrates de Emily Wilson. Aparentemente, es un repaso a la muerte del personaje y a las distintas imágenes que ha generado a lo largo de la historia, llegando incluso a la imagen popular de nuestro día.

Plato’s is the accepted account; what we didn’t learn about in school was Xenophon’s version of Socrates, a dullish wiseacre who gives banal advice about moderation, diet, exercise and self-control to a receptive populace. Only his wife, Xanthippe, is unappreciative of his common-sense views. Wilson engages too with the Socrates of Aristophanes, a fraudulent, word-chopping boffin, whose satirical depiction in The Clouds provides an excellent introduction to Socratic philosophy. Under the headings “Knowledge and Ignorance”, “Socratic Irony”, “Wisdom Is Not For Sale”, “Happiness, Choice and Being Good”, Wilson explains the essentials of Socrates’ credo. At the same time, she shows how Plato’s account of them dovetails with the charges laid against Socrates by the Athenian state: charges of failing to worship the city’s gods, introducing new deities and corrupting the young. Wilson deftly lays bare the political tensions in Athens in the aftermath of the unsuccessful war against Sparta when its democracy was in a precarious state. Anxiety was sparked by Socrates’ relationship with Alcibiades, the playboy who had profaned the Eleusinian Mysteries and thus had probably incurred the wrath of the gods. Wilson shows very clearly how Socrates’ strangeness, his notorious ugliness, and his practice of a profession normally associated with foreigners, all combined to make him a troubling figure for the ordinary Athenian.

This is a superb book. I picked it up by chance and have been gripped. Socrates, ‘the Jesus Christ of Greece’ as Shelley dubbed him, comes to most philosophers via Plato. Emily Wilson, a classicist, provides a lively overview of the numerous Socrates that have existed for different thinkers at different times. These include the hen-pecked master of self-help platitudes described by his pupil Xenophon, the absurd figure that appears in Aristophanes’ The Clouds, the tyrant-loving chatterbox despised by Plutarch, the man of integrity admired by Voltaire and Diderot, the drunken reveller in the Monty Python song who was ‘a bugger when he’s pissed,’ and the unthreatening and decidedly un-socratic Socrates of Phillip’s Socrates’ Café (less gadfly, more nice bloke – see my previous post on this). Along the way she makes astute interpretations of images of Socrates’ death including the famous painting by David and even analyses the medical effects of different types of hemlock to determine whether Plato’s description of Socrates’ progressive loss of feeling in the Phaedo is a santised version of what must have happened (the answer is probably not).

Ya está en la cesta de compra.

Bohnanza, de Uwe Rosenberg (Mercurio). Excelente juego de cartas donde los jugadores se dedican al cultivo de alubias diversas. Cada jugador dispone de dos huertos donde puede ir cultivando plantas del mismo tipo. Cuando le resulta más conveniente, puede recoger lo sembrado y convertirlo en dinero. También es posible, la verdad es que es imprescindible, realizar intercambios con otros jugadores. Una de las particularidades del juego es que es obligatorio jugar la mano en el orden en que se recibió, lo que te lleva a buscar formas de deshacerte de esa carta que te impide llegar a la que realmente quieres. Las propias cartas son también el dinero del juego, por lo que al cosechar y ganar pasta se va reduciendo además el número de cartas en juego.

Bohnanza, de Uwe Rosenberg (Mercurio). Excelente juego de cartas donde los jugadores se dedican al cultivo de alubias diversas. Cada jugador dispone de dos huertos donde puede ir cultivando plantas del mismo tipo. Cuando le resulta más conveniente, puede recoger lo sembrado y convertirlo en dinero. También es posible, la verdad es que es imprescindible, realizar intercambios con otros jugadores. Una de las particularidades del juego es que es obligatorio jugar la mano en el orden en que se recibió, lo que te lleva a buscar formas de deshacerte de esa carta que te impide llegar a la que realmente quieres. Las propias cartas son también el dinero del juego, por lo que al cosechar y ganar pasta se va reduciendo además el número de cartas en juego. Hive: La Colmena, de John Yianni (Crómola). Se trata de un juego para dos jugadores. Cada jugador dispone de una serie de piezas hexagonales que representan insectos. Cada insecto se puede mover sobre la zona de juego de una forma diferente y por tanto sirve a un fin estratégico diferente. Cada jugador dispone de una reina y el objetivo del juego es mover las piezas hasta dejar encerrada la reina del contrario. Se aprende a jugar en poco minutos y es uno de estos juegos para devanarse el cerebro. Además, la partidas son francamente rápidas. Uno de los detalles más interesantes del juego es que las piezas están fabricadas de un plástico duro bastante agradable al tacto, por lo que se puede llevar a cualquier parte y jugar en cualquier lugar, incluso en la playa con viento. Por esa razón dentro de la caja viene una cómoda bolsa para su trasporte.

Hive: La Colmena, de John Yianni (Crómola). Se trata de un juego para dos jugadores. Cada jugador dispone de una serie de piezas hexagonales que representan insectos. Cada insecto se puede mover sobre la zona de juego de una forma diferente y por tanto sirve a un fin estratégico diferente. Cada jugador dispone de una reina y el objetivo del juego es mover las piezas hasta dejar encerrada la reina del contrario. Se aprende a jugar en poco minutos y es uno de estos juegos para devanarse el cerebro. Además, la partidas son francamente rápidas. Uno de los detalles más interesantes del juego es que las piezas están fabricadas de un plástico duro bastante agradable al tacto, por lo que se puede llevar a cualquier parte y jugar en cualquier lugar, incluso en la playa con viento. Por esa razón dentro de la caja viene una cómoda bolsa para su trasporte. Los Pilares de la Tiera, de Michael Rieneck & Stefan Stadler (Devir). Con este juego entramos ya en el territorio de lo juegos de cierta complejidad. La idea es ir construyendo una catedral y precisamente la partida termina cuando se completa el edificio (que se va levantando, con piezas de madera, en medio del tablero). El jugador debe administrar sus recursos lo mejor posible para poder ir construyendo su parte, para lo que dispone de un número limitado de trabajadores y el dinero que haya podido ganar. Sobre el tablero, muy bonito, hay múltiples opciones, aunque, por desgracia, no puedes hacer uso de todas las que quisieses. Organizarse y pensar son las claves de este juego. Hace un tiempo

Los Pilares de la Tiera, de Michael Rieneck & Stefan Stadler (Devir). Con este juego entramos ya en el territorio de lo juegos de cierta complejidad. La idea es ir construyendo una catedral y precisamente la partida termina cuando se completa el edificio (que se va levantando, con piezas de madera, en medio del tablero). El jugador debe administrar sus recursos lo mejor posible para poder ir construyendo su parte, para lo que dispone de un número limitado de trabajadores y el dinero que haya podido ganar. Sobre el tablero, muy bonito, hay múltiples opciones, aunque, por desgracia, no puedes hacer uso de todas las que quisieses. Organizarse y pensar son las claves de este juego. Hace un tiempo  Príncipes de Florencia, de Wolfgang Kramer & Richard Ulrich (Excalibur). Un juego de gran elegancia donde el jugador representa a un príncipe del renacimiento. La idea es ir mejorando el palacio, con la intención de ir atrayendo a artistas e intelectuales para lograr puntos de prestigio y dinero. Para ello, el jugador debe ir cerrando diversas obras cuya dificultad, y también valor, se incrementa a medida que avanza la partida. Al principio, parece difícil de entender, pero gran parte de su complejidad es ilusoria porque a la primera ronda se entiende perfectamente lo que hay que hacer. Su verdadera complejidad radica en que hay muchas cosas a hacer y no hay recursos suficientes para hacerlas todas. Un juego muy satisfactorio.

Príncipes de Florencia, de Wolfgang Kramer & Richard Ulrich (Excalibur). Un juego de gran elegancia donde el jugador representa a un príncipe del renacimiento. La idea es ir mejorando el palacio, con la intención de ir atrayendo a artistas e intelectuales para lograr puntos de prestigio y dinero. Para ello, el jugador debe ir cerrando diversas obras cuya dificultad, y también valor, se incrementa a medida que avanza la partida. Al principio, parece difícil de entender, pero gran parte de su complejidad es ilusoria porque a la primera ronda se entiende perfectamente lo que hay que hacer. Su verdadera complejidad radica en que hay muchas cosas a hacer y no hay recursos suficientes para hacerlas todas. Un juego muy satisfactorio.  Puerto Rico, de Andreas Seyfarth (Devir). Y cuando se habla de elegancia de un juego, Puerto Rico tiene que salir. Cada jugador es el administrador de una plantación colonial que debe ir desarrollando para ganar puntos de victoria. Hay muchas formas de hacerlo, desde construyendo edificios, que a su vez ofrecen ventajas, hasta enviar productos a la metrópolis. Probablemente el aspecto más curioso de Puerto Rico sea su sistema de personajes. En su turno, el jugador elige un personaje de entre los disponibles y ejecuta esa acción con cierta ventaja. A continuación, los demás jugadores pueden ejecutar la misma acción sin la ventaja. Así hasta el final de la ronda. Es decir, si nadie escoge a cierto personaje, la acción de ese personaje no se ejecuta. Deliciosamente retorcido, diría yo. Puerto Rico, número uno en el ranking de BoardGameGeek, es un firme candidato.

Puerto Rico, de Andreas Seyfarth (Devir). Y cuando se habla de elegancia de un juego, Puerto Rico tiene que salir. Cada jugador es el administrador de una plantación colonial que debe ir desarrollando para ganar puntos de victoria. Hay muchas formas de hacerlo, desde construyendo edificios, que a su vez ofrecen ventajas, hasta enviar productos a la metrópolis. Probablemente el aspecto más curioso de Puerto Rico sea su sistema de personajes. En su turno, el jugador elige un personaje de entre los disponibles y ejecuta esa acción con cierta ventaja. A continuación, los demás jugadores pueden ejecutar la misma acción sin la ventaja. Así hasta el final de la ronda. Es decir, si nadie escoge a cierto personaje, la acción de ese personaje no se ejecuta. Deliciosamente retorcido, diría yo. Puerto Rico, número uno en el ranking de BoardGameGeek, es un firme candidato. Caylus, de William Attia (Edge). Y llegamos al juego más pesado de todos, aunque es algo menos elegante que Príncipes de Florencia o Puerto Rico. Al igual que Pilares de la Tierra, que suelen definir como Caylus-light, la cosa va de construir, en esta ocasión un palacio. Es otro de esos juegos que al principio parece complejo de mecánica aunque en realidad es más simple de lo esperado. Las acciones están divididas en fases perfectamente delimitadas y si uno las tiene claras, no hay mayor problema. En realidad, la complejidad se encuentra en otra parte. Para poder conseguir los materiales para construir el palacio, los jugadores deben ir a su vez desarrollando el pueblecito de Caylus construyendo los edificios necesarios (por ejemplo, arquitectos o carpinteros). Por tanto, es muy importante en cada momento tener claro qué edificios te conviene construir y cuáles no y qué beneficios añadidos podrás obtener (si otro jugador usa un edificio contruido por ti, cobras un «alquiler») y la verdad es que hay muchos edificios disponibles. A mí me gusta bastante, pero no es un buen juego para empezar.

Caylus, de William Attia (Edge). Y llegamos al juego más pesado de todos, aunque es algo menos elegante que Príncipes de Florencia o Puerto Rico. Al igual que Pilares de la Tierra, que suelen definir como Caylus-light, la cosa va de construir, en esta ocasión un palacio. Es otro de esos juegos que al principio parece complejo de mecánica aunque en realidad es más simple de lo esperado. Las acciones están divididas en fases perfectamente delimitadas y si uno las tiene claras, no hay mayor problema. En realidad, la complejidad se encuentra en otra parte. Para poder conseguir los materiales para construir el palacio, los jugadores deben ir a su vez desarrollando el pueblecito de Caylus construyendo los edificios necesarios (por ejemplo, arquitectos o carpinteros). Por tanto, es muy importante en cada momento tener claro qué edificios te conviene construir y cuáles no y qué beneficios añadidos podrás obtener (si otro jugador usa un edificio contruido por ti, cobras un «alquiler») y la verdad es que hay muchos edificios disponibles. A mí me gusta bastante, pero no es un buen juego para empezar.