The Ghosts of Pretty Cello Girls

“The Ghosts of Pretty Cello Girls”

To say that Lena Griffin plays the cello on “The Ghosts of Pretty Cello Girls” is to only tell half the track’s story. This is because half the track isn’t cello.

“The Ghosts of Pretty Cello Girls”

To say that Lena Griffin plays the cello on “The Ghosts of Pretty Cello Girls” is to only tell half the track’s story. This is because half the track isn’t cello.

Radioactive Ming vases echo our toxic dependency on electronics – we make money not art

Last year, the Unknown Fields Division, a nomadic design studio that explores peripheral landscapes, industrial ecologies and precarious wilderness, travelled to Asia to follow the path of the symbol of globalization: the massive container ship. The group came back with amazing stories, images, videos and with a set of radioactive Ming vases made from the toxic waste of our electronic gadgets.

Each object is made from the amount of toxic waste created in the production of three items of technology – a smartphone, a featherweight laptop and the cell of a smart car battery. Besides, the vases are sized in relation to the amount of waste created in the production of each item.

Rare Earthenware – Full Film from Toby Smith on Vimeo.

Lo que más me ha gustado deHow Not to Write About Smartphones and Spain · Global Voices no es lo que dice del uso de los teléfonos en España (que puede ser más o menos interesante) sino más bien el poner en evidencia nuestra tendencia a tratar los lugares relativamente lejanos como a) totalmente uniformes y b) como extraños en sí mismo.

Es una tendencia habitual de la ciencia ficción, donde viajar a un planeta lejano es como ir a un lugar con climatología y ecología simple, donde todo es de una única forma concreta. No hay más que pensar en Star Wars, en la que un número limitado de personajes y escenarios ocupa toda una galaxia, y donde los planetas vienen marcados por: hielo, desierto, agua…

En la ficción puede considerase excusable, pero más grave es cuando lo hacemos con otros países y regiones, cuando recurrimos a una especie de esencialismo primitivo, considerando que sólo ciertas facetas del lugar son representativas y excluimos lo que no nos encaja. Lo hacemos mucho con China y Japón, que no sólo tendemos a considerar culturas monolíticas, sino que además tratamos como territorios lejanos donde suceden cosas extrañas que no podemos entender (y por tanto, cualquier noticia “rara” situada en uno de esos países nos resulta automáticamente creíble sea verdad o no). Otro ejemplo es nuestra tendencia a considerar que lo que pasa en España no pasa en otros países de nuestro entorno, como si el resto de Europa viviese en la utopía.

Básicamente, nos aprovechamos de los lugares lo suficientemente remotos para situar allí el paraíso o el infierno.

Como decía, lo gracioso de este artículo es que trata, y desmonta, una de esas situaciones, pero en la que nosotros somos los protagonistas, donde nosotros somos el objeto de alteridad fantástica y monolítica. Es una buena oportunidad para ver el mecanismo funcionando en sentido contrario:

It’s not often that I speak in Internet, but an incredulous O RLY? escaped my lips. The tweet linked to a column in Pacific Standard magazine, which covers social, economic and political issues in the United States, that asserts “the biggest difference” between how Americans and Spaniards use technology is “that no one seems to be on their phones” in Spain. “What locals were doing instead was talking to each other, loudly and heatedly, continuously,” the Brooklyn-based author writes, his observations based on a trip through Spain and Portugal. “It struck me as the kind of socializing we desire when we bemoan our smartphone ‘addictions.’”

The piece almost reads like a satire of a Western correspondent parachuting into an “exotic” locale and reporting back sweeping generalizations about the place. It portrays Spain—still known to many as the land of the midday siesta, even though only about 16% of the population still take a nap every day—and greater Europe as some sort of 21st-century noble savage, in tune with the natural art of conversation and uncorrupted by the same technology that is turning Americans into bleary-eyed zombies.

But when it comes to technology and smartphone addiction, that’s not the case. “Nobody over there seems to be talking about addiction to technology,” you say? Sure, if you don’t pay any attention to Spanish media and haven’t spent more than a holiday’s worth of time with Spaniards, you could say that. A quick Google search returns more than a few mainstream discussions of the issue (in Spanish, of course).

Una vez hice un vídeo sobre Lanzarote, mi tierra, donde mostraba algunas cosas que hay en Lanzarote (un tigre blanco, por ejemplo) pero que no se corresponden con la imagen de Lanzarote. Sin embargo, son elementos presentes y que además llevan allí mucho tiempo. Recibí algún comentario al respecto, más que nada porque nos cuesta aceptar que los lugares reales rara vez se ajustan a la imagen que tenemos de ellos. Pero es un hecho que la isla ha cambiado mucho desde que yo era niño.

2014 – NERDGIRLS – herstory of electronic music

The “NERDGIRLS Mash by poemproducer AGF 8 March 2014 – for equality, diversity and world peace” includes about 50 artists spanning about 50 years of outstanding, smart, fun, female and pioneering electronic music and is dedicated to my daughter.

Puedes encontrar la lista completa de artistas incluidas. Una hora y algo de música muy entretenida e interesante.

NERDGIRLS Mash by poemproducer AGF 8 March 2014 – for equality, diversity and world peace by Poemproducer Aka Agf on Mixcloud

(vía Nedgirls – herstory of electronic music by Antye Greie-Ripatti | ./mediateletipos))))

Dark Jovian de Amon Tobin.

I made these tracks a year or two ago after binge-watching space exploration films. People have, from time to time, described things I’ve done as “scores for imaginary movies,” which has always irritated me, but on this occasion it’s sort of true.

Even so, what I was really trying to do was to interpret a sense of scale, like moving towards impossibly giant objects until they occupy your whole field of vision, planets turning, or even how it can feel just looking up at night.

Visto en Goldsmith-Ligeti EDM.

2 Simple Rules That Great Readers Live By (But Never Tell)

Son dos reglas sencillas. Pero voy a empezar por la segunda: saber dejar de leer. En serio, si un libro no te gusta es legítimo dejar de leerlo. Lo puedes regalar, abandonar en el banco de un parque o incluso tirarlo a la basura (si el libro es muy malo, lo lógico es tirarlo. ¿Le regalarías a un amigo fruta podrida? ¿Verdad que no? Pues igual). No es obligatorio terminar los libros, por poco que quede para acabar. Un libro tiene que ganarse el tiempo que le dedicas.

Como se decide en qué momento dejar de leer ya es cuestión personal. En mi caso, paro en cuanto sospecho que aquello no lleva a ningún sitio. Como si quedan 10 páginas para acabar…:

The old rule ‘100 pages minus your age’, is a good one here. Life is too short to be stuck in books that aren’t going anywhere, that aren’t adding value to your mind. When you’re young, you have more time, obviously, and you also know less what you need and like. But the costs of dilettantism rise with age.

As you get older, you’ll become a more critical reader–not accepting things just because other people say it is good, or more importantly, not agreeing with an author just because they’ve been published. Authors owe a duty to their reader to marshall their arguments properly, to deliver the goods. If they fail to do this–move on. There are plenty of other writers (historians, thinkers, philosophers, entertainers, leaders, poets, storytellers) willing to step up and take their place.

La primera regla es comprar los libros a medida que te interesan. Así ya están en casa y los puedes leer cuando te entren las ganas. La lógica es que en casa están mejor que en la librería.

Sin embargo, eso cuesta dinero, aunque normalmente los lectores no suelen tener problema para gastar en libros. Pero yo la considero una regla más débil precisamente por la razón que la segunda es cada vez más fuerte: la edad. Con los años vas aprendiendo que tampoco hace falta leerlo todo, que ese esfuerzo tampoco lleva a ningún lado. Es más, que un libro te interese en la librería no significa que vaya interesarte días o semanas después, cuando te pongas a leerlo. Que si los libros se pueden dejar de leer, también se pueden dejar de comprar.

Aunque, confieso que yo tengo grandes problemas para no comprar libros.

The Good Wife es una curiosa serie de televisión que bajo el disfraz de una serie sobre abogados se pone a hacer cosas interesantes y poco habituales en las series de televisión. Por ejemplo, su protagonista no es ninguna santa y a veces se embarca en acciones que chocan con el código moral que dice sostener. También pierde ocasionalmente, a veces de la forma más injusta posible, porque una cosa es protagonizar la serie y otra muy diferente es ser un superhéroe (que es, por desgracia, la tónica actual en muchas series: el protagonista no puede perder de ninguna forma). The Good Wife se disfraza de convencional para poder ser diferente, mientras que series como True Detective (cuya banalidad final es parodiada en algunos de los momentos más divertidos de The Good Wife con una serie dentro de la serie que la protagonista ve ocasionalmente) fingen ser diferentes para poder en el fondo hacer lo de siempre y mandar el mismo mensaje de siempre.

Pero aparte de los temas que trata y cómo los trata, The Good Wife también hace otras cosas diferentes con la estructura de la serie. Hay momentos en que la serie parece consciente de ser una serie de televisión y tiene clara las convenciones de una serie. Y en ocasiones, con un brillo de niño revoltoso en los ojos, no duda en jugar con ese conocimiento.

Es estupendo, por ejemplo, ese momento cuando un presentador dentro de la serie anuncia que van a pasar a publicidad y es el episodio en sí el que pasa a los anuncios (lo que recuerda un poco a “I’m not Gary”). O, como dije antes, el comentario sobre la banalidad de otras series —los monólogos seudofilosóficos y hueros o la insistencia en la pesada carga del hombre blanco— que la protagonista mira con diversión.

Y también el sonido. The “Negative Music” of The Good Wife se centra en ese aspecto, cuando un vistazo al interfaz de un sistema de edición resulta ser todo un comentario sobre a) la simpleza del periodismo y b) el cuidado con el que la serie se toma esos detalles.

In “Loser Edit” we watch as the bit of career-recap news is first pitched as a generally favorable overview and then, with the sudden arrival of a slew of damaging emails, as an act of ambush journalism. When the timbre of the still-in-progress story shifts from biography to admonition, the producer of the bit is shown back in the studio with her editor. Earlier in the episode they had left the Florrick character alone in color, against an otherwise black and white photo. Now they switch the emphasis, leaving her alone in black and white, amid a color setting. We watch as, with a simple shift in color coding, they entirely alter the meaning of the photo. The Good Wife is the rare show on television that shows people working on computers in a manner that actually is how people work on computers. We see colors being adjusted and photos being manipulated and text being edited with everyday tools.

And at this moment in “Loser Edit,” the editor dips into a folder of generic background music and switches to a file titled “Negative Music” from one titled “Positive Music.” The sheer, brazen laziness of the action — the sad binary of “positive” and “negative” — speaks volumes of the journalist and her ilk, and though it’s a split-second instant in the overall episode, it also speaks volumes of the intricacy of The Good Wife and the attention of the folks who make it.

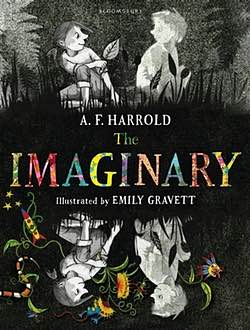

Rudger es un niño imaginario amigo de una niña real llamada Amanda. Amanda, haciendo uso de una imaginación vivaz y casi infinita, creó a Rudger un día, dentro de su armario. Desde entonces son amigos inseparables, viviendo todo tipo de aventuras en los mundos conjurados por la imaginación de Amanda.

Rudger es un niño imaginario amigo de una niña real llamada Amanda. Amanda, haciendo uso de una imaginación vivaz y casi infinita, creó a Rudger un día, dentro de su armario. Desde entonces son amigos inseparables, viviendo todo tipo de aventuras en los mundos conjurados por la imaginación de Amanda.

Le viene un poco de familia, porque la propia madre de Amanda tuvo un amigo imaginario —un lanudo perro grande que hablaba— cuando era niña. Por desgracia, ya no lo recuerda, porque hay cosas que no están hechas para los adultos.

Cosas como los compañeros de juegos imaginarios.

En cualquier caso, Amanda es una niña atrevida, deseosa de comerse el mundo, que se lanza a toda empresa como si fuese la más importante. Rudger es digamos su equilibrio. Mucho más tranquilo, dispuesto a seguirla donde sea, siempre disponible para cargar con las culpas.

Todo va bien hasta que un día aparece un misterioso hombre, Mr. Bunting, que para mantener su larga existencia se alimenta de seres imaginario. En concreto, de seres imaginarios que están empezando a desvanecerse porque sus compañeros reales empiezan a olvidarles. Y tras una serie de vicisitudes, Amanda sufre un accidente y de pronto olvida a Rudger, quien se encuentra huyendo de Bunting y a la vez viendo cómo va poco a poco difuminándose.

Comienza así la historia donde nos encontramos a otros muchos seres imaginarios, visitamos el lugar donde viven, exploramos la relación de Mr. Bunting con su propia compañera imaginaria (una niña que parece sacada de una peli de terror japonesa), conocemos las distintas formas que puede adoptar la imaginación de los niños y comprendemos por qué hay seres imaginarios mejor adaptados a un cierto niño.

A.F. Harrold no ha escrito tanto una celebración de la imaginación como un canto a la imaginación infantil y al lugar que ocupa en el desarrollo vital. En este libro, haber imaginado es mucho más importante que poder seguir haciéndolo y en ningún momento se censura a los adultos por no poder ver a los otros seres (que, por cierto, son los suficientemente corpóreos como para poder ejercer cierta influencia física en el mundo). De hecho, si hay un mensaje, sería que aferrarse al mundo infantil, por maravilloso que sea, no es sano. En todo caso, visitarlo ocasionalmente.

Las ilustraciones, de Emily Gravett, son generalmente en blanco y negro, pero usan de forma muy efectiva el color cuando resulta necesario (en ocasiones, las propias páginas pasan del blanco al negro, dependiendo de la necesidad). Esas transiciones reflejan muy bien el mundo de la imaginación infantil (donde todo lo que piensas se manifiesta de forma real) y ayudan enormemente a crear la atmósfera del libro.

Como casi todas las historias por y para niños, hay un elemento de terror. No es que realmente dé miedo, pero sí que la desaparición (o el desvanecimiento) está muy presente. Como la narración cambia el punto de vista de Rudger a Amanda, nos queda la sensación de seres que piensan sobre el mundo, por imaginarios que sean. Cuando un compañero imaginario desaparece, definitivamente sabemos que la niñez ha quedado atrás.

Como deliciosa historia sobre la infancia y la imaginación, The Imaginary es muy recomendable.

On Kawara-Silence es una retrospectiva del artista en el Guggenheim de Nueva York (hasta el 3 de mayo. Hay que darse prisa) que incluye una performance de una de sus obras más curiosas: One Million Years.

En realidad, lectura de una parte, porque One Million Years es una serie de veinticuatro obras (dividas en pasado y futuro) que detallan fechas (2 millones de años en total, un millón de años para el pasado y un millón para el futuro). La performance consiste en que dos personas van leyendo las fechas.

Brendan and I read at a steady pace, he the odds and I the evens (Kawara’s instructions), a healthy pause hanging in the air between each one. This seems fitting given that each number represents a whole year, each line an entire decade. We read and swiftly cross out our numbers with pencils as we go, using rulers to keep ourselves on track, but even then we stumble. Brendan says “seven thousand seven three …” by accident, and I look down at the abyssal page, suddenly struggling to find my number and remember how it’s actually spoken. “Seven — hundred — seventy-three … ” And then as quickly as we trip, we regain our stride.

So much performance art is built on a foundation of inspired persistence, and one of the beauties of One Million Years is that it offers that experience to those who would normally just watch. Thirty minutes into my hour I had to pee and still hadn’t figured out how to sit comfortably in my chair, but I knew I had signed an invisible contract with On Kawara (as well as a physical one with the Guggenheim), so I continued reading years. There is a kind of freedom in being forced to stick with something past the point when you’d normally quit. You adapt and crudely make your own meaning. I tried, as much as I could, to look up when I spoke my years, making eye contact with museum visitors, offering them my numbers as I would my hand: a gesture of affinity. And I tried to enunciate, projecting the unfathomable past into the mystical modernist spiral, hoping my delivery would be worthy of these pre-human years, of the artist who brought them into the present, and of the building that’s currently serving as their home.

Como añadido, decir que siempre he creído que On Kawara era un artista que habría que tener muy en cuenta en conjunción con la idea de Big Data.